Mountain-Keeper

by Hye-Kyung Stella Kang

Readers’ Choice Award, Summer Writing Contest 2023

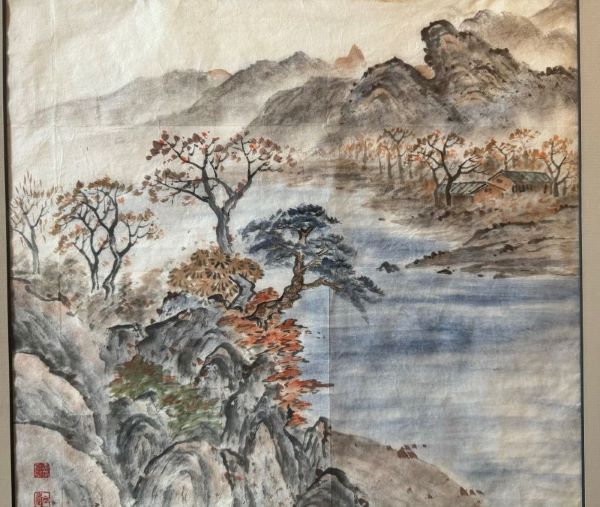

Painting by Dr. Lee (Kang family heirloom)

Today is ChuSeok, the Mid-Autumn Festival. Outside my Seattle window, a slate-gray October sky makes me ache for the sapphire autumn sky of my youth in Seoul. In Korea, ChuSeok is a national three-day holiday to allow people to travel to their hometowns to pay respect to their ancestors and celebrate with family. But I am at work like any other Thursday, slogging through grading student papers on reparations and answering emails from my dean about budget projections. Being an immigrant means that I can’t celebrate my traditional holidays. To get an official day off to cancel classes, I must wait another eight weeks—until the day when descendants of European migrants celebrate their ancestors.

Sipping my morning coffee, I yearn for cinnamon-perfumed sujeonggwa. My last ChuSeok celebration in Korea, more than forty years ago, started with that sweet, amber-colored persimmon elixir served at breakfast. I was ten years old and excited for the big holiday, feeling pretty in my new magenta velvet dress and my hair neatly braided and tied with a matching bow.

After breakfast, my extended family gathered at the home of my eldest uncle, the patriarch. Adult women, like my mom, aunts, and older cousins’ wives, were dressed in their new hanbok, especially made for the holiday. As ladies moved to greet one another, the shimmery silk fabric with delicate embroidery gently swirled and fluttered like cherry blossoms dancing in the spring breeze. Kids trailed moms in their own holiday clothes. Adult men in handsome bespoke suits gathered in a separate circle by the garden, smoking and speaking convivially.

After my eldest uncle’s greetings, a caravan of cars carrying nearly forty family members took off for the ancestral village. The ancestral village was about an hour away from my father’s hometown, Gunsan, a port city in the southwestern region of Korea that was known for excellent seafood and rice wine. My father’s family had owned a rice wine company that grew into a giant conglomerate by the mid-1970s.

As our car headed out of the city and rode toward the rural village, the landscape changed. Concrete buildings and asphalt roads gave way to ochre dirt roads, dusty poplar trees, and rice paddies with dark, skinny men unbending themselves from the golden crop to peek at the line of shiny sedans passing by. The briny ocean scent of the port city similarly gave way to the deep, fecund scent of the farmland. Recoiling from an unfamiliar smell of the working earth, I breathed through my linen handkerchief to filter out the smell.

Jagged peaks of the ancestral mountain in the background of the pleasant, low curves of ceramic or thatched roofs of village houses greeted us as we approached the village. I recognized the mountain-keeper’s house by the tall trees laden with red-orange persimmon fruit set against the deepest cobalt blue of the autumn sky. Surely the ripest of those fruits will become plump and sweet dried persimmons, dusted with powdered sugar and skewered on bamboo sticks, layered by dozens in a gift box, to be sent from the mountain-keeper to my and my uncle’s families.

The mountain-keeper was a man who took care of my family’s ancestral land: the mountain where generations of my paternal ancestors were buried and the large farmland that surrounds it. In exchange, I believe, the mountain-keeper and his family were allowed to grow and harvest whatever they needed—rice, vegetables, fruits—and to raise livestock on our land. I don’t know how long ago his family had been hired by my father’s family, but it seemed like an old arrangement. So old that no one questioned it.

“Mom, how did Uncle Mountain-keeper end up working for our family?” I once asked my mother. I had been packing my stuff to put away before going off to college and had come upon an old picture. The magenta velvet dress I was photographed in reminded me of my last family ChuSeok in Korea.

“I think his family always worked for your dad’s family.”

“You mean, like since the Korean War?”

“Oh, before that. And probably before the Japanese occupation.”

“Do you mean they worked for us since the Joseon Dynasty??”

“Maybe.” She paused. “No one’s ever asked about that.”

I have no idea what the mountain-keeper’s name is. We as children referred to him as Sanjigi Ahjussi (Uncle/Mr. Mountain-keeper). I don’t remember how adults addressed him. I remember that the mountain-keeper and his wife had a few sons and daughters and maybe a grandmother. I am not sure; I did not really see them, even though they were there. The mountain-keeper was on the farthest periphery of my consciousness. He and his family were part of the landscape that I encountered once a year on ChuSeok.

The mountain-keeper and his family were standing in front of their house to greet us when we arrived.

“Good morning, sir. How have you been?” The mountain-keeper stepped forward to greet my uncle with a bow. His family, behind him, also bowed.

“Very well. How are you and your family?” Uncle smiled and extended his hand to shake the mountain-keeper’s hand.

“We’re well, sir, thanks to you. The harvest will be very good this year.” The mountain-keeper eagerly shook Uncle’s hand with both of his hands.

“Good. Glad to hear that. Shall we head to the mountain?”

Uncle’s eyes were already on the mountain, looking past the mountain-keeper’s family. In my memory, this same conversation and scene replayed every year.

As we started ascending the mountain, the mountain-keeper walked ahead of us along the path so he could clear off any debris or snakes that might make our climb to the mountaintop uncomfortable. We followed him on a well-worn path winding up toward the peak that draped a white, wispy cloud over its neck.

My paternal ancestors were buried in that mountain. As we climbed a gradual slope of the mountain, my eldest aunt (“Big Auntie”) told us children the family history, as she did every year. According to the family pedigree book, our branch of Kangs traced its origin to Kang MinChum, a famed general during the Koryo dynasty, circa 1000 AD. Trained as a scholar, he was not much of a warrior but proved an excellent strategist; he led his troop to defeat the enemy during a war against the Mongolian invasion. As a reward, he was given the title of Eun Yeol Gong, which became the name of our branch, as well as a large vassal of land in Jinjoo.

By the time Big Auntie concluded the story with the usual commandment, we were nearly at the top of the mountain. “You are the twenty-sixth-generation children of the Eun Yeol Gong branch of Kang clan of Jinjoo. You must take pride in our family’s history and live your lives to honor our family. Do not disappoint your ancestors! Always remember that you are from a noble family and behave accordingly!”

When we reached our ancestors’ burial site on the mountain, we were greeted by a breathtaking view. According to Feng Sui, burying one’s ancestors in an auspicious location guaranteed good luck and prosperity for the descendants. And the opposite was also true; choosing an inopportune plot could bring disasters. Our ancestors’ graves were in plots that were deemed highly auspicious: facing the sun and overlooking a river, perched high to be guaranteed not to be flooded.

The patriarch uncle bowed and expressed gratitude to one ancestor after another, stopping at each grave, starting from the top of the mountain and moving downward. We followed our uncle until we were through with all the ancestors. I can’t remember what else we did other than listening to our uncle and bowing deeply like he demonstrated for us. I don’t remember Uncle offering food and drink to our long-departed ancestors, which was the tradition. He must have broken with that tradition because our grandmother had converted to Christianity in the early 1900s. American missionaries banned Korean Christians from practicing what they deemed an ancestral worship, a pagan act. Whatever the ceremony entailed, it seemed to take forever to me as a little kid. But I did not dare say a thing. I knew that it was an important event for the Eun Yeol Gong branch of Kang clan.

After the ceremony at the mountain, we headed down to the mountain-keeper’s house where his family served us sumptuous lunch. There were three large tables: the men’s, the women’s, and the kids’. The tables were laden with special holiday dishes like galbijjim with its sweet, savory braised meat falling off the short ribs and melting in the mouth; glistening pieces of soy sauce and honey-glazed chicken; whole ginger-and-scallion steamed fish; five varieties of savory pancakes, and seven kinds of vegetable namul that looked like rainbows. We ate those delicious banchan with newly harvested rice and a deeply satisfying bowl of seaweed and beef soup. After lunch, the mountain-keeper’s wife brought in plates of fruit—slices of red-orange jewels of persimmons, translucent white spears of juicy, crunchy Korean pear, and tart-sweet apples cut to resemble rabbits—and sweet rice cakes for dessert. Lunch was my favorite part of ChuSeok, not just because of the delicious food, but also because it was one of few times in the year when all our extended family members were eating together and enjoying our time as the Kang family.

But who labored over those delicious dishes and sumptuous dessert? As a child I never thought about the countless hours of work the mountain-keeper’s wife must have put in to prepare, serve, and clean up after the feast. And where were the mountain-keeper’s family during our time at their house? They were not seated at the table with us. Where was their table? Did they eat their lunch after we left the village? What was it like for the mountain-keeper’s wife to prepare a feast for the table at which she and her family had no seat? Why did I never question their absence at the table?

I never paid attention to what the mountain-keeper’s family’s ChuSeok might have been like or where and when they had their lunch. They were part of the infrastructure that made my family’s ChuSeok experience pleasant, just as electricity and plumbing made our daily lives comfortable. Their existence was assumed, not considered. The mountain-keeper was part of the package that made up our family’s privilege as the old-money upper class in the 1970s Korea.

The mountain-keeper was also part of the long-standing class relation; as landowners, generations of my family controlled the livelihood of those who worked our land. I don’t know whether the mountain-keeper received any other payments beyond the use of land and the house. Having enough land to grow rice and a large house to live in, even if the land and the house belonged to someone else, was considered an enviable situation in the early 1970s when Korea was still a developing country. The fact that my family let them keep all their harvest was considered a generous deal since most landowners demanded a large share of the crop.

But it seems an unjust deal to me; their labor never produced generational wealth for them but rather built and enriched ours. (When I learned, in college, about the source of the generational wealth gap between white and Black Americans—the legacy of enslavement economy—I recognized the parallel. Although the mountain-keeper’s family were not enslaved, the generational wealth gap was unmistakable.)

The truth is that my family was neither interested in nor needed what our ancestral land produced. Our family and the mountain-keeper’s family lived in opposite corners of the country that was bifurcated between rapidly industrializing cities and economically languishing rural villages. As the Korean economy pulled farther and farther away from its traditional agricultural base, so did my family from our ancestral land. By the early 1970s, no one in my extended family lived in the ancestral village. Our land, to which generations upon generations of my family had been attached, had become just another financial asset by my father’s generation. Now that everyone in my father’s generation has passed, I’m not sure if my cousins could even recognize each ancestor’s grave without the mountain-keeper’s guidance. Are my ancestors saddened by their descendants’ alienation from our land?

It was the mountain-keeper and his family who had a true relationship with our land. They were the ones who worked the land with their hands and knew every peak and valley of our mountain. They were the ones who cut the grass on my ancestors’ graves and looked after their tombstones. Did the mountain-keeper’s ancestors resent having to share their descendants’ devotion, even after death? Did the mountain-keeper’s family go to their ancestors’ graves early in the morning before we arrived? Did they begrudge, behind their quiescent smiles, our annual intrusion upon their lives as part of the payment for their use of the land?

~~~

It has been nearly forty years since my siblings and I immigrated to the U.S. with my mother, following my parents’ bitter divorce. Mom got full custody, which allowed us to leave the country, but the trade-off was that we were severed from my father’s family—and their wealth. Without the protection of class privilege, and being unfamiliar with the new country’s laws, Mom fell for a scam and lost all her money within the first year of immigration. We plummeted down the U.S. economic ladder to poverty and took decades to climb back up half-way to middle class.

As a teenage immigrant, I learned that my family’s upper-class background in Korea meant nothing in the new country. The only thing Americans wanted to know was where I was from, but then it didn’t matter where it was. I was often confused with another Asian immigrant girl from a completely different ethnic background. More frequently, though, I seemed invisible. I worked several low-paying jobs (childcare, hotel cleaning, and overnight shifts at residential care homes, in addition to my work-study job at the college library) to support myself through school. In those jobs, I was invisible to my employers and customers. The guests at the hotel bar barely lifted their feet as I mopped their spilled drinks on the floor. Some said, oh, I didn’t see you there, when I asked them—in a voice calibrated to be as unobtrusive as possible—to please lift their feet. Most simply moved their feet without acknowledging my presence. I was just a pair of hands attached to a mop. At my childcare job, parents would openly talk about how Asian immigrants brought “disgusting habits” to the country while I fixed their children peanut butter and jelly sandwiches.

I doubt those parents and hotel guests literally failed to see me. Those sandwiches didn’t appear out of nowhere and the mop didn’t clean the floor by itself. I was erased out of the picture because I was inconsequential beyond my labor. They saw what my labor produced but not the source of labor. This is the very reason why I did not “see” the mountain-keeper and his family while I enjoyed the fruits of their labor. My class privilege had trained me to erase their presence. The shadow side of the indoctrination to take pride in my family’s aristocratic background was to not see those who were “not our class.” They were simply irrelevant, just as I, an immigrant woman working in low-wage jobs, was invisible.

Privilege is more than an “invisible knapsack of advantages” as Peggy McKintosh conceptualized it in her article, “White privilege: Unpacking the invisible knapsack,” in 1989. Privilege is part of the complex ballet of structural inequalities. And it is not a solo dance; it is a pas de deux with marginalization. McKintosh is right that privilege makes unearned advantages seem invisible to those who have them. But it also pushes people without those privileges to margins where they are no longer seen or heard or counted. Having privilege means that your experience becomes the human experience, and your ways of being are accepted as the culture. The flip side is erasure of the presence of marginalized people: their history, experiences, needs, contributions, and desires. This is why I am working on ChuSeok; as an immigrant of color, my holidays simply do not appear on any “American” calendars. And this is why, even in Korea where ChuSeok is a major holiday, my family’s celebration of our ancestors took the center stage while the mountain-keeper’s was relegated to off-stage.

~~~

My coffee has grown cold on my desk. I need to get back to my lesson plans. I look at today’s topic: reparations for African Americans. I wonder what reparations might look like for the mountain-keeper and his family. What might constitute a fair share of the Kang family’s wealth for them? I am not sure. But acknowledging my family’s economic subjugation of generations of his family may be the first step. And asking them what they might consider a meaningful action may be the next.

I realize that this is a futile exercise since I have no communication with my father’s side of family and no claim on the family’s wealth. But what about the wealth of a country that was built on exploitation of “cheap” labor? In the last forty years, Korea has risen to the thirteenth largest world economy and touts one of the most well-educated populations in the world. Far from a “developing” country of the 1970s, its rapid growth in GDP and global cultural influence are considered miraculous.

But has the shining success of Korean economy changed the old class relations? Did the mountain-keeper and his family receive a fair share of the national success? Did his children become the first generation in his family to go to college, find a high-paying job, and leave the mountain-keeping occupation behind? I hope so. Economic success of a country would be hollow unless it changed old class relations. Otherwise, we are still haunted by the same ghost of economic struggle and control.

I imagine the mountain-keeper and his family celebrating ChuSeok without the intrusion of my family this year. The mountain-keeper, now a grandfather, greets his children and grandchildren who traveled from the city for the holiday. With a big smile on his lined face, he stands in front of the house that he owns. Young men and women in beautiful hanbok rush out of their shiny sedans, and grandkids in bright holiday clothes run to embrace their harabuji.

“Welcome home! How was the drive? How have you been?” He asks his adult children, hugging his grandkids.

“We are well, Dad, thanks to you. The kids are doing very well in school.”

“Good. Glad to hear that. Shall we go pay respect to your grandparents? Mom made all her specialty food to offer to their spirts, and I have this good rice wine to pour over their graves so that their spirit will stay warm on cold nights.” His eyes are shining with affection and pride for his children and grandchildren.

After the ceremony at the grave site, they will sit around a table laden with their favorite food and share a holiday meal together as a family. After dessert, grandkids will chase after dragonflies under the persimmon trees, and their grandma will pack freshly-made dried persimmons in gift boxes for her children to take back home. No one will miss the Kangs; we will be appropriately irrelevant. Then, both the mountain-keeper’s and my ancestors may be at peace.