The Clan of Good Cats

by Rachael Quisel

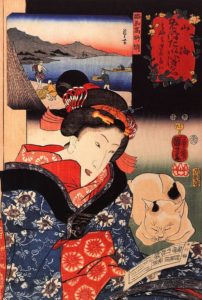

Woman Reading the Paper With Her Cat by Kuniyoshe

My laptop plays a video of a veterinarian who recommends pricking the ear four times—jab jab jab jab—to get enough blood. Her actor cat is, of course, docile and untraumatized.

Apollo swishes his tail. I ready him for the stick, rubbing his cold ear between my cold fingers. We are many months into the COVID-19 pandemic. The ill-timed onset of his disease means I’ve become his hands-on vet. He’s not used to being sick yet. I’m not used to doctoring him.

I prick his velveteen ear. Thin blood squeezes out. The once forbidden kitchen counter is a makeshift examining table, with red sharps bin, med log, and glucose monitor. He engulfs a tuna-pungent treat, then I pill-gun pancreatitis medicine down his throat.

He’s not the only sick one in the room. Like some oven from hell, the disease that’s always lurked within me has recently flared on. Voilà! I’m now an over-baked ham. A singed croissant. I ignore the pain that flickers on and off in my hands, my organs. I don’t let panic overtake me. Not when I have a sick cat to care for. Not today, proverbial Satan.

To my horror, I see that I botched it. The holes in Apollo’s ears don’t produce enough blood for a reading. Is his glucose too high or low? Over and over, I stab his other ear. My cartilage empathically stings.

Apollo crouches low, presses tight against my chest. He does the cat equivalent of grinning and bearing it. He emits just one, quiet cry. My good cat. I’d like to say I never mess up like this again, but I do..

* * *

A chill seeps into my legs from the metal examining table. My rheumatologist advises me to avoid catching viruses.

“Viruses, even vaccines, trigger your disease.”

She doesn’t say how bad this flare will be. My worst-case scenarios hang stiff in the air between us.

Suddenly flashbacks emerge of moments I usually keep tucked away. My grandmother’s death at fifty-six; my mother becoming disabled at thirty-six—my age now. Both had the same blood results as mine.

I crawl off the examining table. Numb lips, tunnel vision, closed-off ears. It’s happening again. My hand masks my hyperventilating mouth. I make a hard knot of myself in a chair.

The doctor’s words wind around and around my neck. I want so much to yowl in her healthy face, to hiss. But I don’t. I want to be a good cat more..

* * *

Months pass, Apollo gets used to being sick, and I get used to appointments. When the radiologist arrives, I flash my canines, and he shrinks away. Or maybe I only imagine this because there’s no way to see my teeth behind my mask.

He escorts me to a fluorescent-lit room. There’s a massive, donut-shaped machine at its center.

“It’ll be over before you know it,” he says. He straps me into the scanner. Would Apollo cry if he were here instead of me? I decide he wouldn’t, and I paw off water from my hot face.

With a mechanical buzzing, the machine’s wide mouth swallows me whole. And the radiologist is right, I don’t feel a thing..

* * *

At home, the kitchen is tipped on its side. Apollo’s chilly nose is bumping my cheek. An invitation back into the clan of good cats. I stroke his shorn belly fuzz. And just like that, I’ve returned to my body.

How did I get on the floor? I stand up and clean the area where Apollo didn’t make it to the litter box. I feed him and wait to see if he vomits. Into a syringe, I draw the correct amount of insulin. One by one, I tap out the bubbles.

While I inject, I lean in. I want him to tell me that he doesn’t feel a thing. Or that the insulin feels like a cool breath under his skin. But there’s no comment. Instead, he offers up his signature scent, purple lupine flowers, and a headbutt demanding pets. I scratch all the good spots.

Now that the stick is done, he extends his time on the countertop for as long as possible. Into the sudsy sink, then the stinky produce box, then pawing crumbs behind the toaster. It’s an opportunity to play with the forbidden, and he takes advantage. He has no shame.

I marvel at how the core of him, the best part of him, remains intact, even as his body eats itself from the inside out. What will hold fast in me and what won’t? Kidneys, vision, sanity? Even still, maybe I can be as good as he is about all of it.

From the fridge, I snag the chocolate chip cookie dough, then drop a kitty treat on the floor. One for you, one for me.

We will go through this ritual twice a day for the rest of his life. Together, we’re one tiny, virtuous cycle, one love story, one quiet anecdote of survival. Two beings who aren’t losing themselves even when they feel all is lost. Maybe, right here, right now, that’s all we need to be.

A Cat Dressed As A Woman Tapping the Head of an Octopus by Kuniyoshe