Walt Whitman on the Metro

Marie Manilla

Walt Whitman is disappointed in me. I’d just spent three days in D.C. reading The Wound Dresser: a series of letters written from the hospitals in Washington during the War of Rebellion. While traveling, I like to read books set in the cities I’m visiting: Dave Eggers’ Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius in San Francisco, Barbara Kingsolver’s High Tide in Tucson in Arizona, Helene Wecker’s The Golem and the Jinni in Lower Manhattan.

I’d been to D.C. numerous times, but on this visit I intended to conjure Whitman’s ghost. I sat on the Mall imagining what that area looked like one hundred and forty years earlier, that city of mud and malaria. I strolled the Capitol Grounds where Whitman had tipped his hat to Lincoln when their paths crossed. The admiration was mutual. I found locations, if not actual houses, where Whitman once boarded. The penultimate highlight was visiting the National Portrait Gallery, the former Patent Office where Whitman had worked for a time. He’d also acted as a nurse inside those walls when it served as one of several Civil War hospitals in the nation’s capital. There he befriended ailing soldiers. In addition to wiping brows and treating festering wounds, Whitman wrote letters for them, brought treats of tobacco and ice cream, offered tender kisses. He was the last face many of them saw—a bearded angel. As I strode the bright galleries I pictured cot after cot lined up, wedged in. I filled the silence with moans and cries, the clattering of surgical instruments, and the echoes of Whitman’s footsteps. The gruesomeness altered his health and mind, but he kept vigil daily. Such was his service to humanity. Peter Doyle, his eventual Washington lover, was a former Confederate soldier. Those men could mend relationships even if the country could not.

The day I toured the Portrait Gallery there was an exhibit of artifacts from Lincoln’s second inaugural ball. On display were Mary’s ball gown, Abe’s top hat, an invitation, a Bill of Fare listing several meat courses: terrapin, beef à-la-mode, veal Malakoff, fois gras, tongue en gelée. I hope Lincoln ate well that night. Less than six weeks later he would be assassinated just around the corner. Whitman was inconsolable. Still, he remained in the city for another eight years, working government jobs, writing elegiac poems to his captain and the country he loved even as it disappointed him.

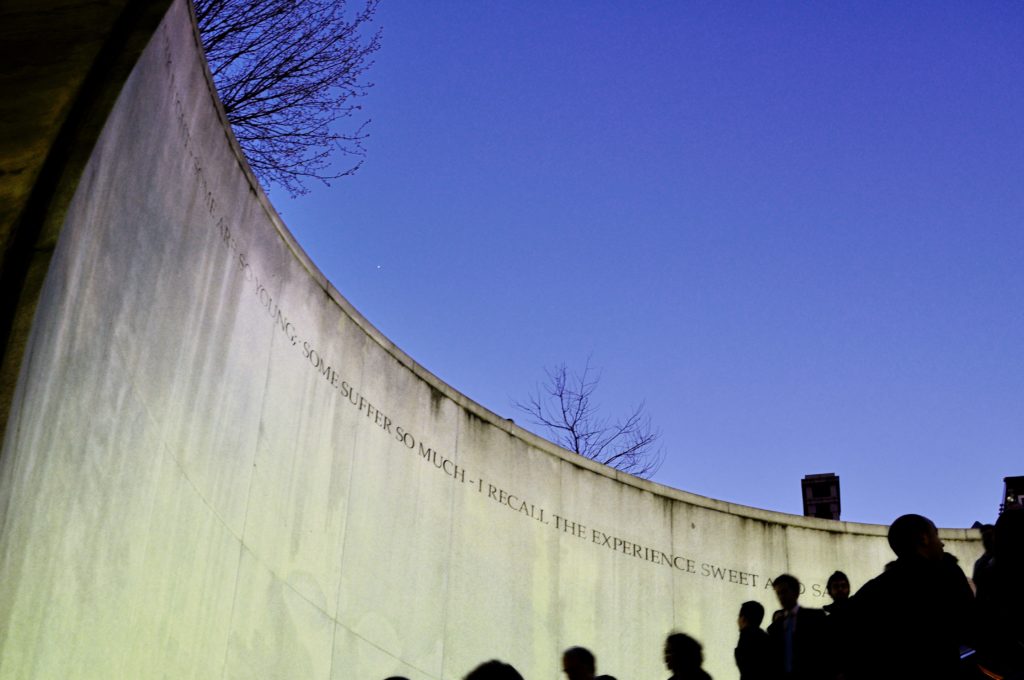

The city paid Whitman homage by inscribing his poetry in at least two Metro stations: Archives-Navy Memorial and Dupont Circle, the latter the last stop on my itinerary. It’s a steep ascent from the underground through a granite bowl or bowel. Three escalators make the one-hundred-eighty-eight-foot climb easier at a thirty-degree angle. The escalators were broken the day I emerged and it was murderously hot. The sun unforgiving. Still, I trudged up step after step with hundreds of commuters, all sighing and sweating, likely counting steps in our heads. When I finally reached the summit I cleared the masses, caught my breath, and turned around. There, etched into the concave granite circling the gaping Metro entrance were lines from Whitman’s poem “The Wound-Dresser”: “Thus in silence in dreams’ projections, returning, resuming, I thread my way through the hospitals; the hurt and wounded I pacify with soothing hand, I sit by the restless all the dark night—some are so young; some suffer so much—I recall the experience sweet and sad.”

I felt mournful too, and found a nearby coffee shop where I read Whitman’s letters and let his melancholy wash over me.

An hour later I tucked the book into my purse and headed once again to the Metro’s open mouth. The escalators still weren’t functioning, but this time gravity was on my side. As I made my way down I commiserated with pedestrians jammed in the stalled middle escalator trying to ascend. It was quitting time, and they were eager to get home. There was a clog in the queue about midway down. As I approached, I saw a stylish young woman, model beautiful. Model thin too, who could have used a plate of terrapin or duck liver. Both hands gripped the rubber railing as she tried to pull her way up all one-hundred-eighty-eight feet. “I can’t do it!” she moaned. She looked left and right for assistance. “I can’t do this!” The only looks she got were ones of disdain that she’d become an impediment. Business men and students and nannies edged past her. Some scowled at her beauty; assumptions were made. Poor princess can’t even climb the stairs. I was one of those. As I tumbled past her going in the opposite direction I saw her pleading eyes but did nothing. I’ve offered stray dogs more compassion. At the bottom, I rushed along the corridor toward the tracks.

Inside the train, I slid into a seat, hugging my purse. The doors closed, the car lurched, and we zoomed away. I settled in for the ride, my eyes drifting across the aisle where three seats up sat Walt Whitman: grizzled white beard, rumpled suit, long hair poking from beneath a dented hat. He was reading The Post, with President Obama’s photo prominently displayed. How far we’ve come, I thought. I hugged Whitman’s letters and smiled at the idea of him endlessly riding the Metro in the city he loved, roaming the streets, leaving his dust for us to collect beneath our boot-soles.

Then an image of that girl still clawing her way up the escalator. Walt would have helped her. Would have gripped her arm and tugged her up. “Come along, dear.” He’d probably have escorted her to a cafe for coffee and a Danish.

The weight of my inaction pressed me into my seat. I still have so far to go. We all do. Our hatred of other, our horrendous crimes and petty jealousies that we must overcome.

I’ll do better next time, Uncle Walt.

Photo by Lisa Luo

www.jiaimagery.com

2 comments

Marie Manilla says:

Sep 16, 2019

Thank you, Sherri! I appreciate your kind words.

Sherri Moshman Paganos says:

Aug 19, 2019

I enjoyed this piece so much. I love how you weave Whitman — his life and poetry — into your D.C. visit, and what he taught you. Well written, nice ending.