Doyle Family 1894

Another Mary Doyle

Jacqueline Doyle

“There she is, Mary Doyle, and another right beside her. … Come from Moycullen

from Westmeath and Usher’s Quay. Come from Poulnamuck, Gweesalia, and

Tourmakeady. From Clongeen, Collooney, and Cahermacrea. From Kilkelly and

Kilmeena, Ballina and Bonniconlon.”

Sonja Livingston, “A Thousand Mary Doyles”

Ladies Night at the Dreamland

I see her on the steamer bound for America, hands gripping the railing as she inhales the salt air. It’s cold on deck, perhaps early spring. Mary doesn’t know whether it’s salt spray or tears that make her cheeks so wet. She’s young and alone, eager and afraid, ready for the unknown. Her mother always called her a daydreamer. A boy in her village used to tease her and stole a kiss at the Limerick County Fair, but he’s in Bristol now. She’s a good girl. She’s prepared to work hard. She’d like to wear fine clothes, she’d like to live in a grand city, she’d like to fall in love and get married. She’d like to have children.

Whitecaps foam on the gunmetal gray water. Waves slap against the sides of the ship. Who could have imagined an ocean so vast? A firmament so dark? When a shaft of sunlight pierces the roiling clouds, illuminating the gray sky with shimmers of unearthly light, it feels like a message from above. Her heart sings. Hosanna! She makes the sign of the cross and begins a prayer of thanksgiving to the Blessed Mother. Hail Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with thee.

* * *

She’d probably never been outside County Limerick before. She must have been homesick and full of dreams. I can only imagine how my father’s paternal grandmother Mary Doyle felt. The facts I know about her are few enough. She was nineteen years old when she joined the droves of Irish girls still leaving by the boatload for America. Mary Doyle by marriage, she was born Mary Agnes Hayes, left Ballingarry for New York in 1880, and married R. Patrick Doyle eight years later in North Tarrytown, just up the Hudson. Much older than Mary, “Paddy” had emigrated from County Kilkenny and had already been working in the U.S. for seventeen years when they married.

When my father began his research into the Doyle family history, he gave Mary’s wedding ring to me–a slender gold band, almost weightless, with two arcs of delicate scallops surrounding five tiny stones, chips really, three miniscule diamonds and two miniscule sapphires. My parents had two missing diamond chips replaced with diamonds from an antique watch and had the ring resized to make it smaller. For almost thirty years I’ve worn it on my left hand as my wedding ring. I’m often aware of Mary when I absent-mindedly rub the back of the ring with my thumb or twist it on my finger. I was nineteen years old myself when I flew to Ireland for my junior year abroad at Trinity College, Dublin, my first time out of the country. Later I completed a Ph.D., took a job in California, six thousand miles from Mary’s birthplace. I’ve never been back to Ireland. And yet, I’ve always felt deeply connected to her.

I resisted my father’s obsession with genealogy when he was alive, what I saw as his immersion in the history of his ancestors at the expense of his relationship to his living family. There were so many unresolved tensions between my father and me. But I’ve begun to reconsider his desire to explore family connections. “If we cannot name our own we are cut off at the root,” Dorothy Allison writes, “our hold on our lives as fragile as seed in a wind.” Mary’s ring reminds me that our lives begin before we are born and continue after we die. The artifacts we leave behind contain the seeds of our histories, which bear fruit long after we are gone. There’s something so intimate about wearing a ring. Something touching me that touched her. Did Mary ever try to imagine me, as I try to imagine her? I have a grown son, but no daughter. Who will wear Mary’s ring after I’m gone?

* * *

Mary and Paddy are standing in front of a jeweler’s window, somewhere in lower Manhattan. She clutches his arm with one hand, holding down her long skirt and petticoat against the gusts of cold wind with the other. She barely notices the chill or the gray, overcast sky. She can hardly believe her good fortune. He’s old, but he’s a handsome figure of a man. He’s got some money put by. He’ll be a good provider. She wonders, fleetingly, about the boy who went to Bristol. About others, long since married, in Ballingarry. What would the girls at home say? Will she ever see her mother again? “Paddy, you shouldn’t,” she says to him. He beams. Puffs out his chest like a peacock courting a mate.

* * *

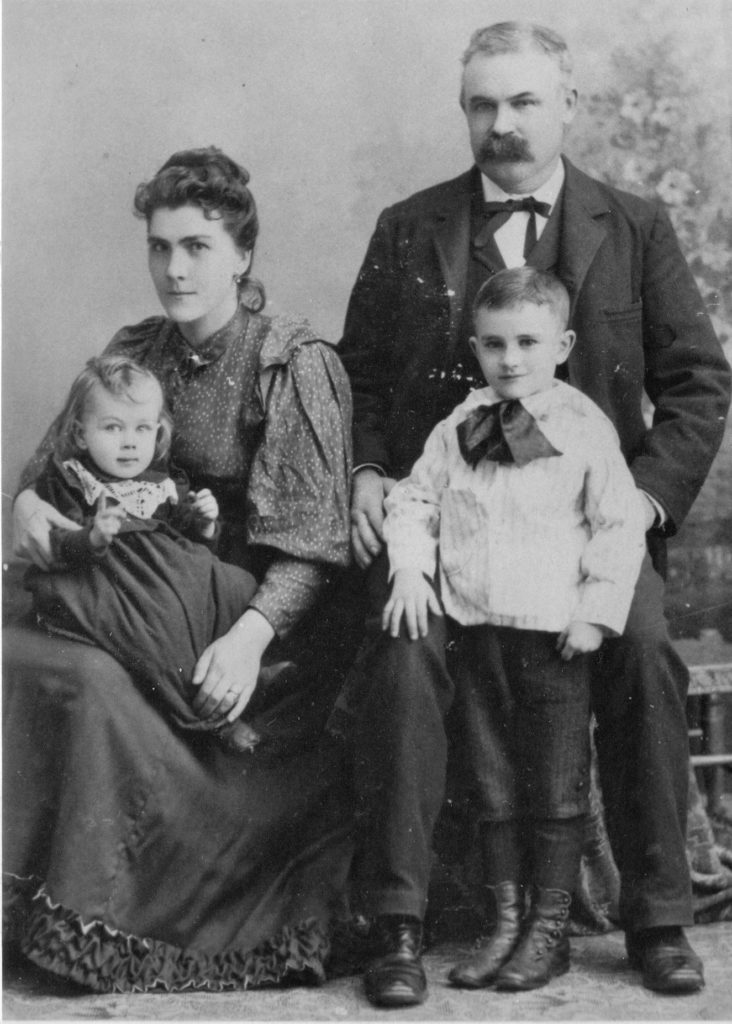

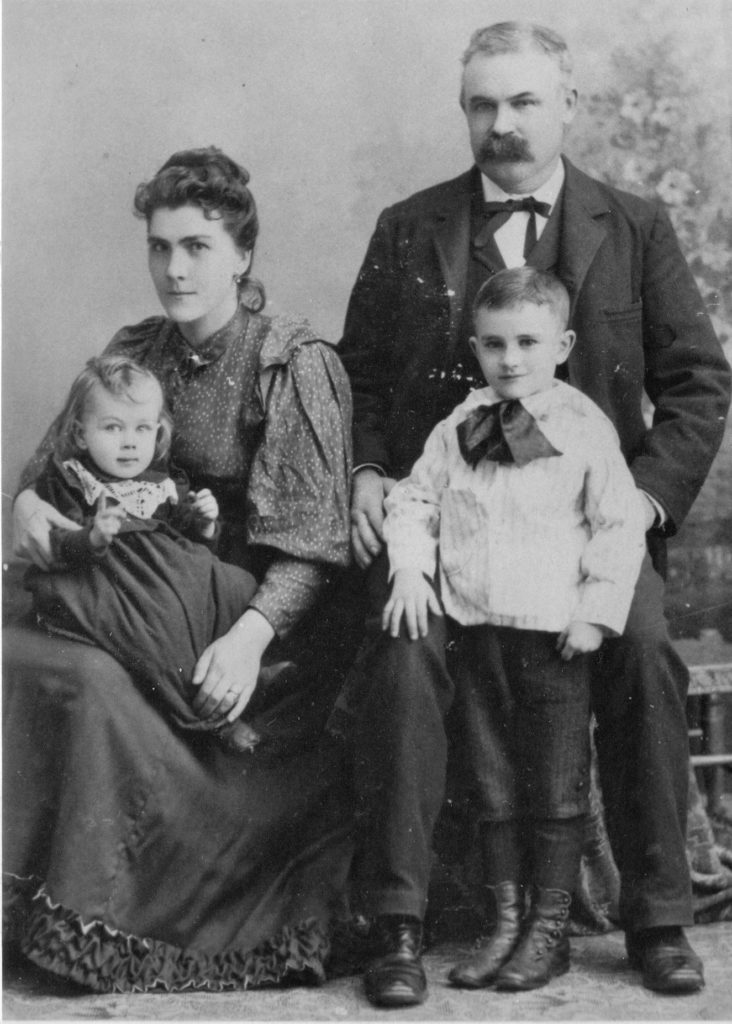

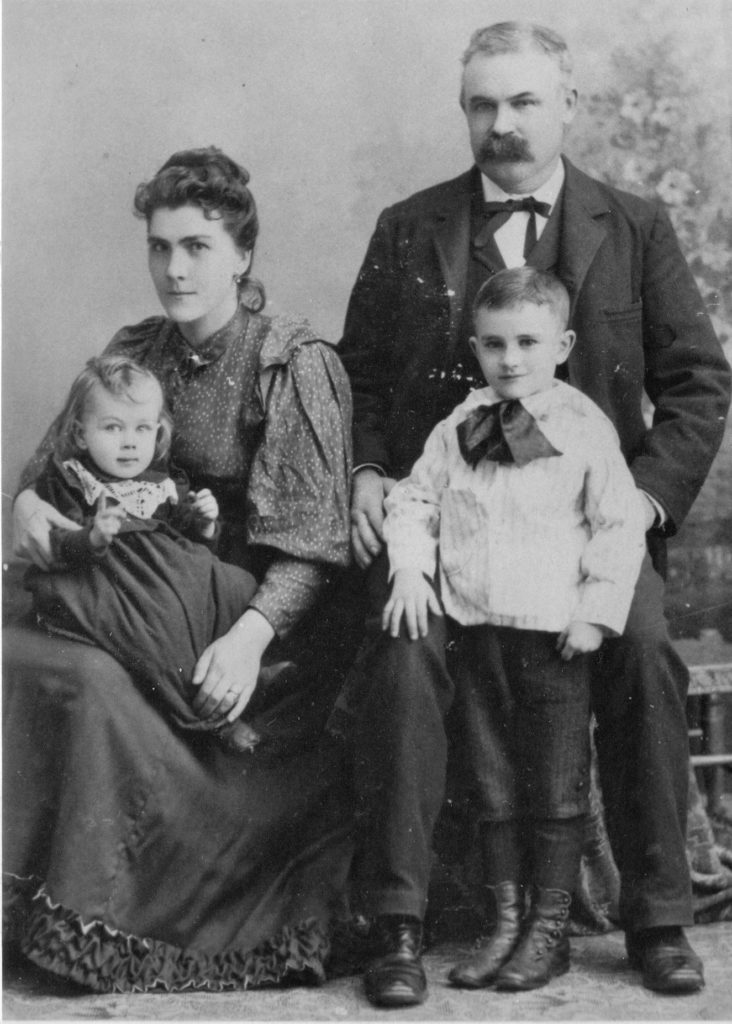

The sepia-toned family portrait, dated 1894, is arranged as many such professional photographs are, with Paddy Doyle, the patriarch, sitting on a high stool that makes him a full head taller than his wife Mary. He is robust, gray haired, with dark eyebrows and a heavy, dark mustache. Young Patrick Edward, my grandfather, must be about six years old. His hair, cut very short, is neatly combed, and his ears stick out as my father’s did. His face is elfin, sensitive, his smile shy. He looks relaxed, one hand on his father’s knee. An infant, John, reclines in his mother’s lap. He wears a dark dress with lace at the collar, and looks more like a girl than a boy with his long blond curls.

It’s Mary Doyle who draws my eye. She sits half turned from the camera. She’s wearing a blouse with leg-of-mutton sleeves, lighter than her plain dark skirt, perhaps a print fabric. She looks slender but sturdy. Her brown hair is gathered on top of her head, curls escaping on her forehead and at the nape of her neck. I can see the ring on her left hand, which clasps her baby’s feet.

Although she is angled away, she stares directly at the photographer, with an expression that is difficult to read. She seems to be withholding something, perhaps only suppressed gaiety, perhaps some other secrets she is not ready to disclose.

* * *

Mary takes off her ring and puts it in her apron pocket. Leans over the washboard and rubs each shirt with a large bar of soap. Up and down, up and down. Hands raw and burning from the lye, she rests them on her swollen belly for a moment before resuming her task. Up and down, up and down. Her arms ache. She pushes stray tendrils of hair away from her face with the back of her hand, wipes the sweat off her face with her sleeve. When she finishes scrubbing the clothes she transfers them to a steaming vat of hot water and stirs them with a pole to rinse them, rinses them again in another vat, lifts them out with a wash stick and immerses them in a third vat of water with bluing, and then wrings them out by hand, one at a time. The basket of clothes she hauls out to the clothesline is so heavy. She feels a sharp twinge in her lower back as she straightens and wonders whether it’s her time already. Paddy will be home soon enough wanting his dinner. And who’ll mind the children until then? She hopes Mary Murphy is home next door.

* * *

Mary was the most popular name for girls of Mary Hayes Doyle’s generation. One historian estimates that one out of three Irish girls christened in the 1860s was named Mary. One million Irish died and two million emigrated between 1845 and 1855, during and following the catastrophic five-year potato famine called Gorta Mó, “The Great Hunger.” Of the remaining six million, almost two million more emigrated in the three decades that followed. Most were single, over half of them female. Thousands upon thousands of Marys crowded the gangplanks to make the overseas voyage to the United States. In Ireland their families and neighbors threw send-off gatherings called “American Wakes” for the emigrants, who were unlikely ever to return.

Even now, the trauma of the Great Hunger and the exodus that followed linger, planted deep in the Irish-American collective unconscious. Mary’s mother would have been one of the survivors of the Famine, which devastated Mary’s birthplace in County Limerick. Paddy, born in County Kilkenny in 1843, would have grown up in the midst of the Famine, though the east of Ireland suffered its ravages far less than the west. Historians report that marriage patterns changed after this period. Before the Potato Famine, twenty percent of Irish husbands were more than ten years older than their wives; after the Potato Famine, the figure was about fifty percent.

Though Mary is about thirty-four in the photograph, she looks younger. Paddy would have been fifty-one years old. What was their life in America like? I don’t know whether my father availed himself of books like Margaret Lynch-Brennan’s The Irish Bridget when he began his research on the Doyles, but recent scholarship about ordinary women’s lives fascinates me. At the turn of the century, the majority of Irish-born women on the East Coast worked ten-to-twelve-hour days, seven days a week, as house servants. Mary probably worked in domestic service. The Doyles were a small family, for the Irish. Infant mortality among the Irish was the highest among all ethnic groups in New York. Did she bear other children and lose them?

* * *

So stern and strict when he got older, Paddy was. Mary shakes her head at the memory as she lowers herself into the rocking chair, rosary beads in her hand. When the children were little, Paddy was more like a fond Granda than a Da. A good provider, not one to take more than a pint or two in the saloon after work, he hurried home to be with them, and they laughed and shouted with glee, climbing all over him like monkeys, looking for the sweets he hid in his pockets, hanging around his neck and from his thick arms.

But later. All he could talk about was money. “Where’s the money coming from,” he thundered at their eldest, who winced and couldn’t answer. So stricken. She’d never forget the look on her firstborn’s face. “The Church would have taken care of you.” Her heart was broken over the two of them, how Paddy closed his heart after young Patrick left the seminary to marry. How Patrick took it so hard. And it was a rough life Patrick led, crisscrossing America, traveling to Africa, South America, leaving his wife, Nan and two boys with kinfolk while he looked for work. “He made his bed,” Paddy said.

That last year of his life, Paddy couldn’t stop talking about the Famine. America in 1930 almost looked like Ireland–ragged men standing in breadlines, men riding boxcars, women with wailing infants, no food or shelter or jobs to be found. Things are better now. She wishes Paddy could have lived to see that. She picks up the rosary in her lap.

* * *

I play with the ring, twisting it on my finger so the stones are centered on top. I wonder what constellation of secrets the five stones hold, more than a century of unwritten history, mute as the stars.

My father told me so little. I know that my grandfather Patrick left the seminary and later married. I don’t actually know how his parents felt about it. Many Irish women were excessively proud of sons who entered the priesthood, so it could well have been Mary Doyle and not her husband who felt betrayed by my grandfather’s defection. Or perhaps neither of them felt that way. Have I invested my great-grandfather with my father’s unforgiving anger and exaggerated financial worries?

I can speculate that the Depression and his itinerant childhood created my father’s intense anxieties about money. My grandfather traveled the U.S. and the world looking for work, often leaving his family behind. My father, Jimmy, and his younger brother, Harry, were sometimes farmed out to relatives. Education, professional success, and economic security were very important to him. I can also speculate that the horrors of the Potato Famine may have created acute anxieties about poverty in my great-grandfather and the generations that followed. Researchers say that ancestral trauma is coded in our DNA and never fully disappears. I’m more frugal than I need to be, always seeking out sales like my Irish-American mother did, concerned about saving for the future like my Irish-American father. I don’t know whether that’s environmental or genetic.

* * *

Mary rocks, waiting for Patrick and Nan and her grandchildren Jimmy and Harry to arrive from Jersey City. Now that she finally has time to rest, her bones ache, and she can hardly enjoy it. She fingers the spot where two stones are missing on her ring, lost in memories of the days when Paddy was still alive, and the children nestled in her arms, smelling like milk, sticky from Paddy’s sweets. Her black-haired grandson Jimmy reminds her of Paddy. So hard working and ambitious. So serious, studious. So American already.

* * *

In search of more facts about Mary Doyle, I’ve managed to unearth a stack of family trees from one of the sagging cardboard boxes of my father’s files in my garage, the product of years of genealogical research involving multiple trips to Ireland and New York. They’re handwritten, in my father’s precise, draughtsman’s block letters, and his handwriting is so familiar that for a moment tears well up in my eyes.

For a long time I scoffed at the twentieth-century Irish-American obsession with family history, including my father’s. Our family was falling apart, it seemed, while he lavished attention on the dead and a semi-mythical past. He’d withdrawn from my brother and me when none of our achievements corresponded to the dreams of upward mobility he’d cherished when we were born. He never got over his bitter disappointment when my brother failed to finish college. I’d completed a graduate degree, but failed to marry the kind of son-in-law he had in mind. He closed himself off for decades before he died. Nearing retirement myself now, maybe I’m ready to forgive him for ambitions so large that his children didn’t measure up. Ready to understand his solitary dreams, his desire to transcend his nomadic, financially precarious childhood and make it in America, I find myself retracing his steps, recapturing his passion for ancestry, his desire for origins and historical certainties in a world where nothing felt stable.

As I smooth out the Doyle family tree, I notice that my grandfather had yet another sibling, a second sister I never heard of–a girl. She would have been the middle child if she’d survived: Catherine Doyle, who died the year that my great-uncle John was born. So the family portrait was taken a year after John’s birth, a year after the death of Mary’s only daughter, Catherine, at the age of two.

I pick up the sepia-toned photograph in the oval frame to study it again, this time more closely. John’s feminine baby clothes, Mary’s firm grip on his tiny feet. The shuttered look in her eyes. It is grief she hides. Not high spirits, as I first guessed.

* * *

The church is cold and drafty. Everyone has gone, but Mary remains on her knees, clutching the back of the wooden pew in front of her. Oh my God, I am heartily sorry for having offended Thee. Did the Virgin Mother embrace little Catherine at the hour of her death? The candles on the altar flicker. The baby stirring in her womb can’t fill that emptiness. Or erase her memory of Catherine’s face, so white and still, all the light gone out of it. Oh my God, I am heartily sorry. What could I have done? What should I have done? Mea culpa, mea culpa, mea culpa.

* * *

That night I have a dream of Mary Hayes Doyle and her lost toddler, but I can’t remember it when I wake up, just the pervasive feeling of sorrow, which stays with me all day. Mary lost not only her child but her birth family and her homeland, her entire past. How did she feel about leaving so much behind?

When I leaf through the dog-eared stack of family trees again in the morning, I’m surprised to discover a Hayes family tree. Only one page, spotty, with many dates missing. When his grandmother died, my father was in his twenties. He must have known her well. I wish he’d written a prose account of what he remembered. What was she like? Did she tell stories? She must have spoken with a brogue. Did she talk about her childhood in Ireland? He went to the Doyle farm in County Kilkenny several times, but I don’t know whether he visited her birthplace in County Limerick in the course of his research. He would have told me if he’d located the Hayes relatives. Still, I wish I’d asked more questions while he was alive.

According to the family tree, Mary Hayes had two younger brothers, yet another Patrick, and Edward. There’s a younger sister who became a nun.

And then a spectral figure rises off the page, startling, unexpected: Catherine Hayes, born the same year as Mary, with no date of death listed.

Mary had a twin?

Her very indeterminateness makes her an uncanny and oddly symbolic figure for me.

Mary must have named her only daughter after her twin sister Catherine. Were they identical twins? They would have known each other’s thoughts, communicated without words. They might have grown up speaking a private language, as twins often do. Every time Mary looked into the mirror in America, she would have seen her sister’s face. She would have seen her out of the corner of her eye, reflected in shop windows as she walked down the streets of New York City. When she mourned the death of her child, she mourned the loss of both Catherines.

So many Irish girls emigrated. Thousands upon thousands. Catherine Hayes could have moved to England or Australia or Canada. She could have joined Mary in America.

But instead I imagine her in Ireland, trading letters for years with her sister. Soulmates, separated by three thousand miles of water. Mary’s Irish self, waiting for her return. Another Mary Doyle of sorts, her spiritual origin preserved, my family’s spiritual origin preserved, with no date of death.

* * *

My father labored to fill in the blank spaces in the family past. An engineer, he privileged facts over imagination, approached history as a science. “I think sometimes that I became a historian because I didn’t have a history,” Rebecca Solnit writes in A Field Guide to Getting Lost, “but also because I was interested in telling the truth in a family in which truth was an elusive entity. It could be best served not by claiming an authoritative and disinterested relationship to the facts, but by disclosing your own desires and agendas, for truth lies not only in incidents but in hopes and needs.” What did my father hope for and need as he immersed himself in family history? That wasn’t something he ever addressed. Was he seeking approval from his Irish ancestors for his self-made success? Was he hoping for continuity when he gave me his grandmother’s ring? Am I hoping for approval and continuity as well? I don’t know how he’d feel about his feminist daughter’s imaginative reconstitution of her matriarchal origins.

Nevertheless, what I’ve found in my search for the true history of Mary Doyle is a connection to my father. It’s as if I’ve released his ghost by studying the family photograph albums he left behind and opening the boxes in the garage. As I imagine Mary’s final reunion with her sister in Ireland, I can feel his presence as well as hers all around me.

* * *

Mary lies in bed with her hands crossed on her abdomen, a rosary lightly wrapped around them. Her wedding ring is loose on her finger. Hail Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with thee. How many decades has she prayed? So many. Blessed art thou amongst women, and blessed is the fruit of thy womb, Jesus. Paddy never prayed, except when baby Catherine was dying. Then he cried, great shuddering sobs. She fingers the crystal beads, disturbed even in her half sleep. She hears her mother’s soothing whisper. “There, there, a chuisle. There, there.” Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us sinners now…. She drifts. She remembers the rutted dirt road in Ballingarry, how red the dirt was. How green the fields that stretched in all directions! Golden Vale, they called it. Now and at the hour of our death. She remembers Knockfierna Hill surrounded by silver wisps of mist in the morning. Lying in bed with her sister under a pile of quilts, their arms wrapped around each other. So cold it was in the morning, so warm in bed with Catherine. Sister of her heart, mirror of her soul. The fields all green and yellow. The sky gray and aquamarine, clotted with moving clouds. The winding dirt road so red. The gentle swell of Knockfierna in the distance. She labors to breathe as she runs toward her sister, who laughs and beckons from down the road. Her heart thumps in her chest, expands. Catherine! She opens her arms as she lurches forward, almost trips and falls. A gentle gust of wind stirs the fields on all sides of her. And now she feels weightless, as if she can fly.

3 comments

Maddie Lock says:

Oct 18, 2018

Beautiful and vivid imagery. I appreciate how you layered your tale, and the way you wove present and past tense. I am also in the process of uncovering my family’s history for a memoir. The challenge lies in uncovering the truths and presenting them honestly while realizing there are many layers to peel away, more than we can hope to ever understand and yet present them accurately while still honoring the memory and the person.

Lewis says:

Aug 6, 2018

Interesting family history as well as details about the Irish Great Hunger. Such an interesting photo, too, of the family makes the essay come alive for the reader.

Genia Blum says:

May 7, 2018

I was attracted immediately to the old family photo, and this became the first piece I read in Under the Sun’s gorgeous 2018 edition. With its sense of nostalgia, it’s almost a partner piece to my own essay in this issue, about my Ukrainian family. Jacqueline Doyle writes skillfully about her Irish ancestors and, with great warmth and tenderness, weaves a gripping story of their lives and struggles. I read with tears in my eyes, and regret that some things can never be known. Beautifully told.